is now

printing is now a 40-year-old manufacturing process that has advanced by leaps and bounds over the past decade, especially in the metals sector, with new materials continually being qualified and printing methods being perfected—allowing creative genius to be realized. We have come across some exciting examples, some of which hold the promise of achieving scale.

For example, MASK Architects, Sardinia, Italy, designed a steel 3D-printed structure of modular prefabricated houses for Nivola Museum, also in Sardinia. The architects foresee living as art and want housing to be beautiful.

Architects Öznur Pınar Çer and Danilo Petta were inspired by a sculpture by Costantino Nivola, called La Madre, to create their Exosteel Mother Nature modular houses.

The studio used a steel 3D-printed “exoskeleton” construction system that supports and distributes all the functional elements of the building. Each house features a hollow central column that works as an energy plant, with attached branches that support three stories.

Each building is self sustaining and can provide energy to the grid of the development. The Energy Tower, which consists of a steel structure, is covered with solar panels, and a section at the top rotates 360 degrees to capture wind energy.

Following successful testing at NASA’s Stennis Space Center of Launcher’s liquid oxygen turbo-pump for its closed-cycle liquid rocket engine, Launcher is working with Velo3D to print its fuel pump, flight turbine housing parts and Orbiter pressure vessels.

“Velo3D really delivered on our turbo-pump, including its 3D-printed rotating impeller, all of which functioned perfectly the very first time at 30,000 rpm, using the first prototype,” says Max Haot, founder and CEO of Launcher.

“Rocket engine turbo-pump parts typically require casting, forging and welding. Tooling required for these processes increases the cost of development and reduces flexibility between design iterations,” Haot says. “The ability to 3D print our turbo-pump—including rotating Inconel shrouded impellers—makes it possible now at a lower cost and increased innovation through iteration between each prototype.”

In its latest application, Uniformity produced a roll cage designed for a solar-powered race car on its in-house SLM 280 2.0 dual-laser powder bed fusion 3D printer. The part will be used on a car participating in the Bridgestone World Solar Challenge, an event for solar-powered cars racing 3,000 kilometers through the Australian outback.

The roll cage was printed with a 30 μm layer thickness to get the ideal surface finish. The vehicle’s engineering team used topological optimization techniques to design the part to ensure strength while reducing weight. The cost and material performance were critical factors, so they replaced carbon fiber with an additive manufactured part made from Uniformity Labs’ AlSi10Mg powder, containing aluminum, silicon and magnesium.

“Our ultra-low porosity AlSi10Mg and print processes allowed the car development team to create a better part quickly, cheaply, and optimized for the necessary weight and safety parameters,” says Adam Hopkins, founder and CEO of Uniformity Labs.

For space applications, every reduced kilo is a direct win for a project’s feasibility.

For space applications, every reduced kilo is a direct win for a project’s feasibility.

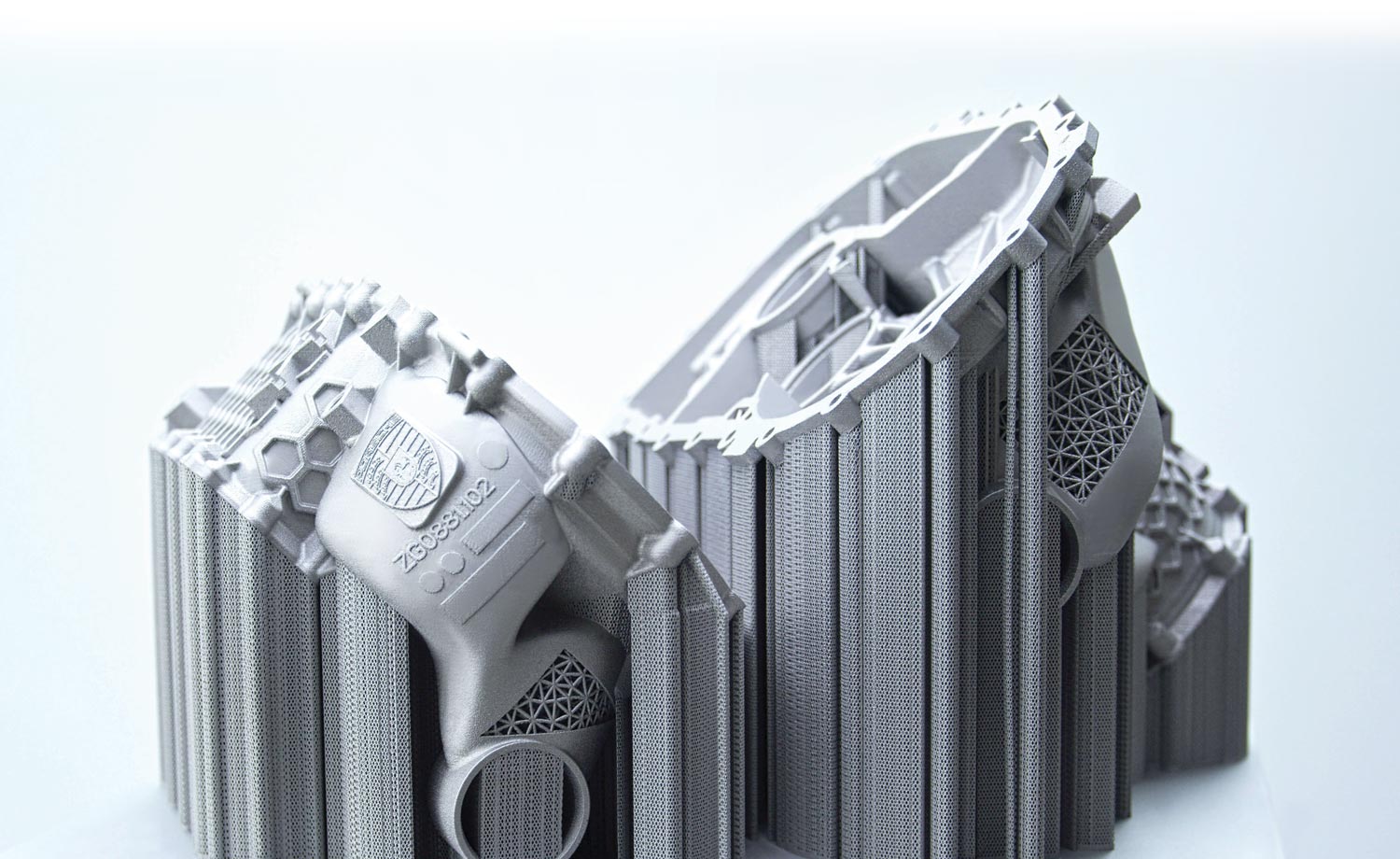

“This proves that additive manufacturing with all its advantages is also suitable for larger and highly stressed components in electric sports cars,” says Falk Heilfort, project manager in the Powertrain Advance Development department at the Porsche Development Centre in Weissach, Germany.

Porsche engineers carried out several development steps at once with the prototype. The AM alloy housing is 40 percent lighter than a conventionally cast part and reduces the overall weight of the drive train by 10 percent.

Thanks to special structures only possible with AM technology, the stiffness in highly stressed areas has been doubled. Porsche continues to use AM to optimize highly stressed parts. With the latest achievement, “our goal was to integrate as many functions and parts as possible in the drive housing, saving weight and optimizing the structure,” says Heilfort. The integration of parts helped to reduce the assembly process by about 40 work steps. This is equivalent to reduction in the production time of 20 minutes, according to Porsche.

MX3D worked with KM Yachbuilders to custom design and print—using robotic wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM)—an aluminum keel that measures 4 by 8 meters (13.1 feet by 26.2 feet).

“As skilled welders become scarce and customization [becomes] the standard, shipbuilders like KM Yachtbuilders are looking for innovative methods to produce unique parts efficiently and cost effectively,” a spokesperson for MX3D states.

“Maritime assets are capital intensive, downtime has financial consequences and the production operations are often situated at remote locations in isolation from repair facilities and spare parts storage,” according to MX3D. “Robotic WAAM offers opportunities in reshoring and accelerates custom, low-cost and fast printing of complex objects. [Using] WAAM, the design and assembly becomes an automated process,” materials can be optimized and assembly costs can be reduced.

a nationwide network.

Our team is here, there and everywhere ready to help when you need it. Let us bring your business the ultimate flexibility and competitive edge so you can deliver the most consistent product to your customers!

The prototype floor section was 3D printed in stainless steel by MX3D to meet efficiency, use and construction constraints. The structure’s web pattern emerged from delineating stress map analysis and optimizing a continuous topology to reduce mass and make maximum use of 3D printing manufacturing methods.

Using grade 308LSi stainless steel, the floor structure took about 246 hours to make. The structure weighs 395 kg and reaches 4.5 meters (14.8 feet) once assembled. The floor consists of six separate segments printed then welded together. The structure is supported by three columns; floor panels are inserted into the structure.

“This was a great opportunity to show the potential of our technology for the fabrication of lightweight metal structures,” explains Gijs van der Velden, CEO of MX3D. “When designing space applications, every reduced kilo is a direct win for a project’s feasibility.”

High-speed 3d printing paves the way to create complex parts that weren’t possible.

High-speed 3d printing paves the way to create complex parts that weren’t possible.

“This is a breakthrough in making 3D printed and sintered parts for the auto industry,” says Harold Sears, Ford technical leader for additive manufacturing. “While the 3D-printing process is very different than stamping body panels, we understand the behavior of aluminum better today, as well as its value in light weighting vehicles. High-speed aluminum 3D printing paves the way for the ability to [create] complex parts that previously weren’t possible with aluminum.”

When printing metals, the final bound metal part must be sintered in a furnace to fuse the particles together into a solid object. The heating process reinforces the strength and integrity of the metal and, while the process for sintering stainless steel is well understood, achieving high densities greater than 99 percent is an industry breakthrough for aluminum, according to Ford.

For decades, heat exchanger designs have remained relatively unchanged. Recognizing the need to unlock new, high-performing heat exchangers, researchers at U of I’s Grainger College of Engineering developed shape optimization software that allows them to identity 3D designs “that are significantly different and better than conventional designs,” says William King, professor of mechanical science and engineering and co-leader of the study.

The team began by studying a tube-in-tube heat exchanger. Using a combination of the shape optimization software and additive manufacturing, the researchers designed fins to be placed internally, which is made possible only by using metal 3D printing. The prototype heat exchanger “has about 20 times higher volumetric power density than a current commercial tube-in-tube device,” says Nenad Miljkovic, a mechanical engineering associate professor who also co-led the study.