LIGHT

new laser cutting machine is a huge investment. When making the leap, it’s easy to be attracted to the highest wattage laser, thinking its cutting capabilities assuredly increase productivity and reduce operating costs. But when laser-cut parts are piling up because the bending or welding department isn’t set up to match cutting volume, how efficiently is that faster-cutting laser fitting into the overall process?

Dustin Diehl, laser division product manager at Amada America Inc., says that it’s human nature to want the most powerful machine—the bigger-is-better mindset. But, “the whole picture is the overall investment. Can you get by with less wattage? There is a lot more to your actual cost per part.”

“First, evaluate what your goals are,” adds Jason Hillenbrand, Amada’s general manager for blanking and automation. “Often, customers think they want the most power, but it’s really about throughput—how many parts you can get through the entire process within a given period of time.”

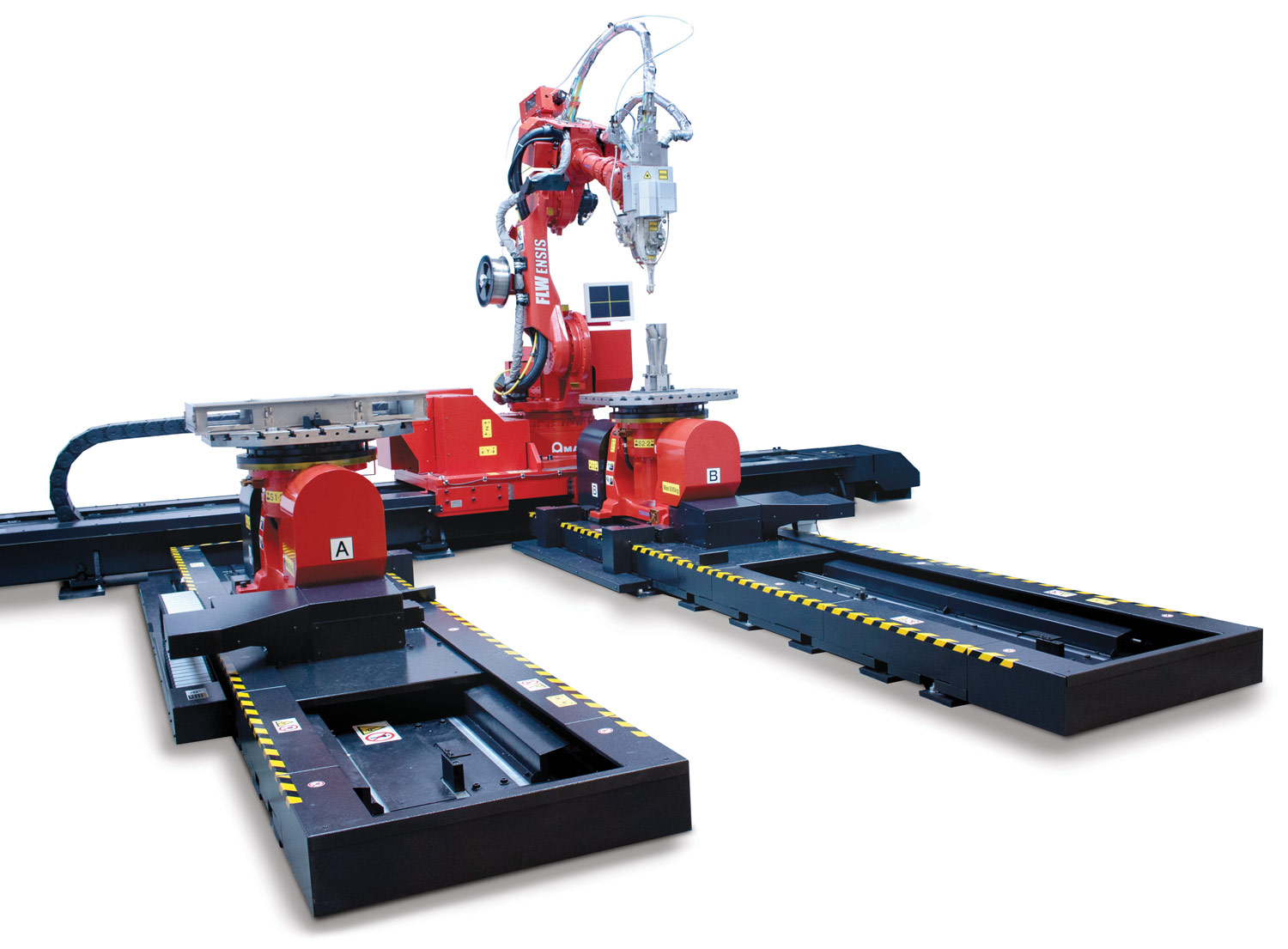

A closer look at actual needs, wants and part mix may reveal that the higher-wattage laser is not the best choice. “We might steer a customer into a little different approach,” Diehl says, “getting them away from a something like a standalone 9,000 kW and moving toward an automated, smaller wattage machine that can actually produce a lot more parts in the same 24-hour period.”

Because laser technology has advanced so much over the last decade, material can be processed a lot quicker, he continues. “Now, you are getting into bottlenecks on the bending side or even assembly and painting. It is becoming necessary to create a solution with automation to make your entire facility run smoother.”

“We know that a standalone machine with an operator that’s hand loading and unloading —using a very good process, which means material is delivered to them and programs are ready to go—you might see a 60 percent green-light-on time. That’s a good environment. Quite often, an operator is his own forklift driver, so he goes and gets the material and brings it back, then maybe has to make a few edits to the program. All of a sudden, that standalone machine is down in the 40 to 50 percent green-light-on time range.”

Often, customers think they want the most power, but it’s really about throughput.

Often, customers think they want the most power, but it’s really about throughput.

He cites a customer he worked with that had been in business for some time and was working with an assortment of older equipment. “It was getting hard for them to bid on work because a lot of the other job shops in the area had already moved into high-speed lasers. Although their processes were comfortable and reliable, they understood it was time to step up their game and be more competitive,” Diehl says.

Knowing that their competition was using higher-power lasers, naturally, this customer wanted a similar machine. “But we looked at their process and discovered that a lower-wattage machine would provide great improvements on the bulk of their work, and that also opened up some capital to improve their press brake technology. Almost a two-for-one.”

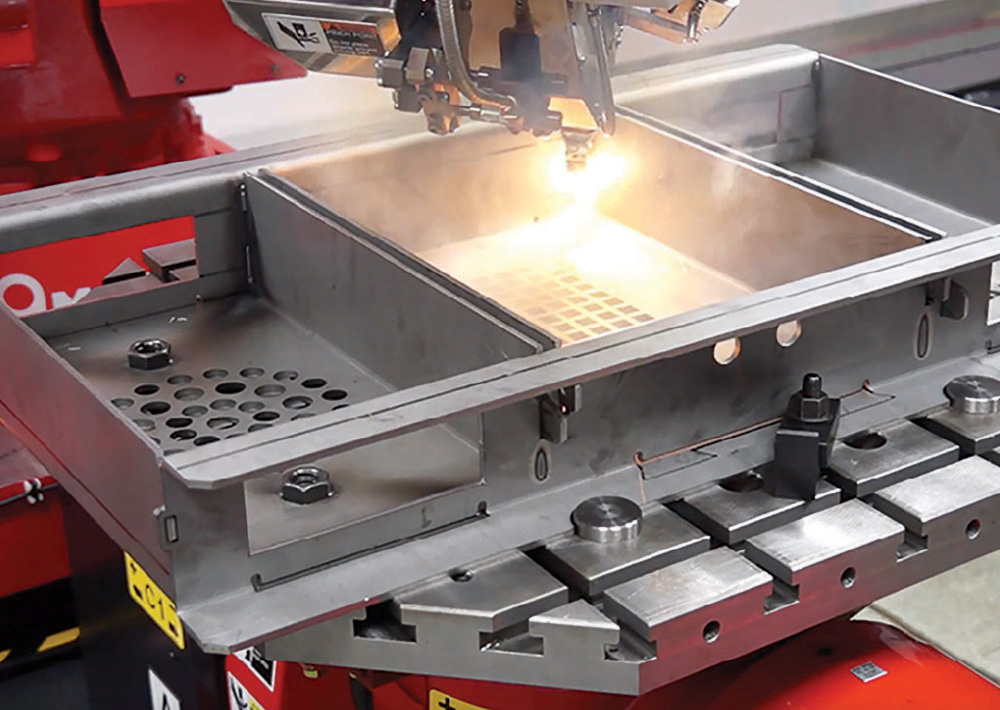

Another customer, a small OEM that makes products from stainless steel, needed an automated system to remove the parts from the laser and stack them without scratching, Picardat continues.

“They were at the point where they needed more operators who could form the parts but, as a small shop, they were concerned about hiring more employees. So they started looking at bending automation.” After the upgrades, the customer cuts parts on the laser, automatically removes those from the skeleton and stacks them for transfer to the bending robots.

“Their existing operators can keep these two bending robots and the laser running while also being able to work on a press brake for any custom parts that needed to be run,” Picardat explains. The increased productivity allowed the customer to grow into a larger supplier in its area. Unlike humans, automation easily completes tasks the same way every time, which can provide hidden benefits. According to Hillenbrand, an Amada customer in California saved hundreds of thousands of dollars in scrap because of how the parts were stacked. “It kept the parts stacked in the same direction, eliminating the operator from accidentally inserting the part into the brake incorrectly. In a manual operations, many times the parts are stacked haphazardly or simply thrown into a box, allowing the parts to be rotated, adding to potential bending errors.”

“Customers who haven’t dealt with automation before have never experienced coming in to a stack of parts waiting for them to go down to bending, go over to welding,” Diehl says. “Once they start getting used to the automation, they want more of it. And that’s a big step.”