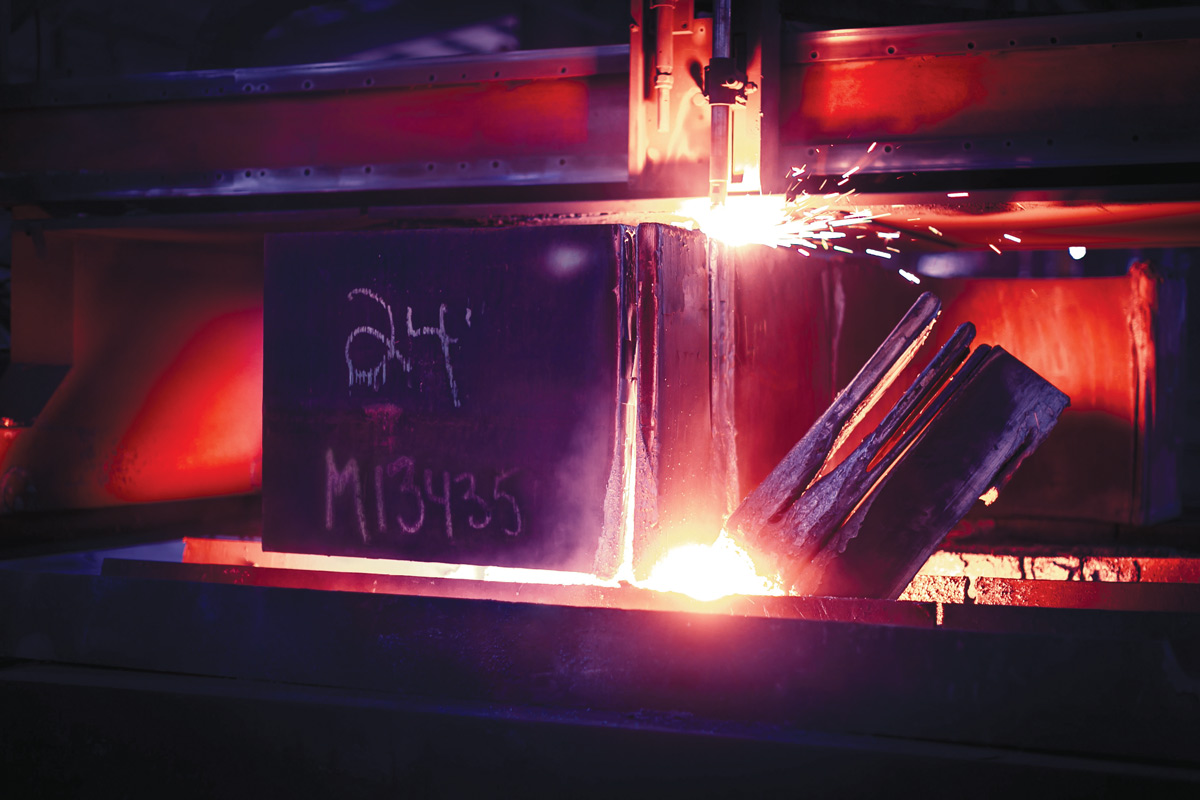

aunched in 2014 with what company President Jim Stevenson calls “the dirty dozen” employees, Churchill Steel Plate now has 50 people working two shifts to keep up with demand.

“We are a very niche business,” says Stevenson. The distributor stocks carbon and alloy steel plate from 0.25 inch through 24 inches thick, but its specialty is processing material 6 inches thick and above. Services include high-definition plasma, flame and saw cutting, furnace treatment, grinding and ultrasonic testing.

When commodity markets move into territory rarely seen in years, a curious person wonders if and how participants have prepared for the unexpected.

“Everything changed, and quickly, during the fourth quarter. We started to see prices increase and lead times extend. That created a dynamic where everyone started to chase inventory and position themselves to get ahead of price increases,” says Andrew Sberna, vice president of sales.

Late last autumn, the leadership team held a series of meetings, and the purchasing department was advised not to worry about the size of the service center’s year-end inventory. “Steve Fleming manages our inventory and makes a value judgment about what to buy,” Stevenson says.

At year end, “the mills are generally slow, and they want to move steel out the door. We made two mill buys. It was a gut feeling. As we sit here today, we wish we would have bought more,” he says. “We were being aggressive in December, and we wanted to replenish and prepare for first quarter. We were positioned pretty well.” However, “we sold out a six- to eight-week supply in half the time.”

we have seen prices increase exponentially, almost on a weekly basis.

we have seen prices increase exponentially, almost on a weekly basis.

we have seen prices increase exponentially, almost on a weekly basis.

we have seen prices increase exponentially, almost on a weekly basis.

“We have a trusted network of suppliers who are key to our success,” says Sberna.

It has been helpful to be a niche buyer that domestic and European steel mills are very familiar with, he says. “We know one another and where the sweet spot is.” All the same, “the price increases have come so fast and furious.”

According to Fleming, “Based on price, based on lead times, the mills may not quote until they are ready to open the order books. And trucking is an issue too. So, it’s hard to get the material.”

Churchill’s business model is highly transactional by design. “We don’t have long-term contract business. Part of managing our supply chain is deciding what to buy even when we don’t have a forecast from our customer. We use intelligence from our sales team and customer history,” Sberna explains.

“The balancing act I have with inventory is that when lead times fluctuate and go out, you have to decide how aggressive you want to be,” Fleming says. “In December, lead times were five to six weeks, and now they are 10 to 12 weeks. If we place a buy overseas, we won’t see that steel until December or January 2022.

“The cost of doing business is up. Gas is up. Drivers and trucking companies are naming their price to take loads. You must adjust accordingly, and you have to pay more to get the material, in order to take care of the customers,” Fleming adds.

Fleming believes that COVID-19 removed a lot of drivers. They took a risk “going into and out of facilities,” and many have “left the trucking industry. There is a shortage of drivers. Yet, carriers are seeing more volume.”

Customers were surprised about the rapid pace of price increases, he says. “Now they are realizing they need to revisit their inquiries prior to placing their orders. We are constantly revising quotes on price and lead times. People are now adapting to what’s going on. They must make sure material is coming in and verify the cost.”

“We look at scrap pricing as an indicator. That is up right now; when it starts to go down, that could change steel pricing,” says Fleming.

“If we do start seeing a scrap price decline, we may pull back a little on the buying and expect mill pricing to turn downward,” Fleming adds.

Sberna says the company will continue to focus on core strengths, including value-added services. “It helps to have a diverse customer base. We give them a near-finished product, and that helps them to serve their own markets.”